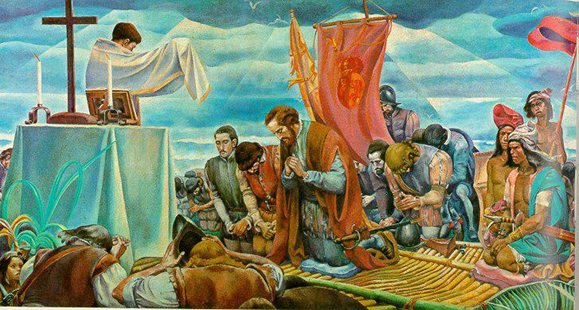

A brief overview of the Philippine Literature during Spanish Times

-Historical Background. Spanish colonization in the Philippines started in 1565 during the time of Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, the first Spanish governor- general in the Philippines. Literature started to flourish during his time. The Spaniards colonized the Philippines for more than three centuries.

Duplo or Karagatan

– is a poetic kind of a game. It is played in the backyard of the house. Usually, an old man/woman starts the game. It is played when there is a man or a woman who died.

Tibag

-the word tibag means to excavate. This ritual was brought here by the Spaniard to remind the people about the search of St. Helena for the Cross on which Jesus died. The Cenaculo – this is a dramatic performance to commemorate the passion and death of Jesus Christ. There are two kinds: the Cantada and Hablada .

Zarzuela

is a Spanish lyric-dramatic genre that alternates between spoken and sung scenes, the latter incorporating operatic and popular songs, as well as dance. The etymology of the name is uncertain, but some propose it may derive from the name of a Royal hunting lodge, the Palacio de la Zarzuela near Madrid, where, allegedly, this type of entertainment was first presented to the court.[1] The palace was named after the place called “La Zarzuela” because of the profusion of brambles (zarzas) that grew there, and so the festivities held within the walls became known as “Zarzuelas”.

The Senakulo (from the Spanish cenaculo) is a Lenten play that depicts events from the Old and New Testaments related to the life, sufferings, and death of Christ. Image Credit. Pasyon. The senakulo is traditionally performed on a proscenium-type stage with painted cloth or paper backdrops that are called telon.

MORO-MORO–The earliest known form of organized theatre is the comedia, or moro-moro, created by Spanish priests. In 1637 a play was written to dramatize the recent capture by a Christian Filipino army of an Islamic stronghold. It was so popular that other plays were written and staged as folk dramas in Christianized villages throughout the Philippines. All told similar stories of Christian armies defeating the hated Moors. With the decline of Spanish influence, the comedia, too, declined in popularity. Some professional troupes performed comedia in Manila and provincial capitals prior to World War II. Today it can still be seen at a number of church festivals in villages, where it remains a major social and religious event of the year. Much in the manner of the medieval European mystery-play performances, hundreds of local people donate time and money over several months to mount an impressive performance. Moro-moro is the earliest form of theater in the Philippines starting in 1650. It is part of their cultural routine when entertaining their visitors

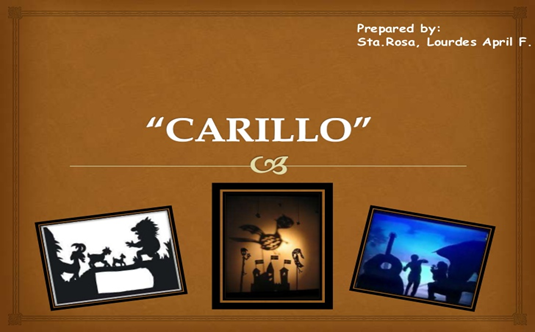

CARILLO

– this is a form of dramatic entertainment performed on a moonless night during a town fiesta or on dark nights after a harvest. This shadow play is made by projecting cardboard figures before a lamp against a white sheet. The figures are moved like marionettes whose dialogues are produced by some experts. The dialogues are drawn from a Corrido or Awit or some religious play interspersed with songs. These are called by various names in different places:

Carillo in Manila, Rizal and Batangas and Laguan; TITRES in Ilocos Norte, Pangasinan, Bataa, Capiz and Negros; TITIRI in Zambales; GAGALO or KIKIMUT in Pampanga and Tarlac; and ALIALA in La Union.

Corrido- (Spanish pronunciation: [koˈriðo]) is a popular narrative song and poetry that form a ballad. The songs are often about oppression, history, daily life for peasants, and other socially relevant topics.[1] It is still a popular form today in Mexico and was widely popular during the Mexican Revolutions of the 20th century. The corrido derives largely from the romance, and in its most known form consists of a salutation from the singer and prologue to the story, the story itself, and a moral and farewell from the singer.

Corrido is a popular narrative song and poetry form, a ballad

Example: Narco Corrido

Children want to be narco

.They see money and power.

Children play in the street,

Dirt stains their feet,

Body covered by a sheet

.A convoy of Escalades,

Narcos in masks with AK-47s.

Children play in the street,

The wrong dream soils their feet,

Body covered by a sheet.

A narcobloqueo playground For Death and Chaparrines.

An old man washes the blood Of children from the street.

He looks like Jesus MalverdeWith a crown of smoke.

Pray to Santa Muerte,

Save them from the Devil.

Children play in the street,

Death stains their feet,

Body covered by a sheet.

Awit- (Tagalog for “song”]) is a type of Filipino poem, consisting of 12-syllable quatrains. It follows the pattern of rhyming stanzas established in the Philippine epic Pasyon. It is similar in form to the corrido. One influential work in the awit form is Florante at Laura, an 1838 narrative poem by Francisco Balagtas.

To Celia

Poem by Francisco Balagtas

If I recall and read again

those days in love’s long-faded script,

would there be not a mark or trace

but Celia’s, imprinted on my breast?

The Celia whom I’ve always

feared might forget our love,

who took me down these hapless depths,

the only reason for this turn of fate.

Again would I neglect to read

the pages of our tenderness,

or call to mind the love she poured,

the bitter struggle I gave for it?

Our sweet days gone,

my love is all that’s left;

ever shall it dwell within

till I’m laid down in my grave.

Now as I lie in loneliness,

behold wherein I seek relief:

each bygone day I revisit, I find

joy in the likeness of your face.

This likeness painted with love

and longing has lodged within

my heart, sole token left with me

not even death can steal.

My soul haunts the paths

and fields you blessed with your footsteps;

and to Beata River and shallow Hilom stream

my heart never fails to wander.

Not rarely now my vagrant grief

sits under the mango tree we passed,

and looking at the dainty fruits

you wanted picked I forget my ache.

The whole of me could only

be intimate with sighs when you were ill;

for I knew as Eden kept a room us,

my hidden hurt was heaven still.

I woo your image that resides

in the Makati river we frequented;

to the happy berth of boats I trace your steps,

among the stones that touched your feet.

All these return before me now,

the joy of years, the blissful past,

where I would soak and steep myself

before I’m caught in brackish neap.

Always I could hear what you would say:

Three days and our eyes won’t meet.

And the eager answer from my leaping heart:

There’s only me but you prepare a feast.

So what was there in our

joyful past that memory could miss:

in constant return the tears do flow,

I sigh and weep: O hapless fate!

Where is Celia, joy of my heart?

Why could our blissful love not last?

Where is the time when just her look

was heaven’s glimpse, my soul, my life?

Why, when we parted,

did this luckless life not cease?

Your memory is death, O Celia,

but in my heart you will not fade.

This long torment you brought,

I couldn’t bear, O departed Joy;

but it took me by the hand to poetry and song,

about a life so trodden low, now lost.

Celia, my messages are mute,

my muse is dumb, her voice faint;

without my taunt she would not speak,

pray listen to me with mind and ear.

This first spring that breaks

from my parched mind I offer at your feet:

deign receive, from this kneeling heart,

even if you won’t savor it.

If all this fell into slur and insult,

my gain is great from invested effort,

if complaint it is you now peruse,

remember, too, it is the author’s gift.

O joyful nymphs of Bai, the placid lake,

Sirens whose voices bring music to my ears,

I come now to your sparkling shrine,

my forlorn muse implores you.

Rise now to shore and field,

accompany with lyre this humble song

that speaks: if fate this life may snip,

its fervent wish is that love won’t cease.

Gleaming bloom of my mind,

Celia whose symbols are M, A, and R;

here I am adoring at the Virgin Madonna’s

altar, F and B, your loyal servant.